Fact Or Fiction: Examining Current Knowledge About The Captive Big Cat Crisis

General information regarding the captive big cat crisis in the United States appears not to have been updated in almost two decades. Much of what is reported portrays the crisis as still being as dire as at the end of the 1990s. Updating our understanding of current captive big cat populations within the country is crucial to informing accurate and effective advocacy and legislation.

Fact or Fiction: Examining Current knowledge about the Captive Big Cat Crisis

12/29/2018 - Rachel Garner

General information regarding the captive big cat crisis in the United States appears not to have been updated in almost two decades. While some of the claims, such as the big cat population numbers, have fluctuated over time, much of what is reported portrays the crisis of privately owned big cats as still being as widespread and dire as at the end of the 1990s. New data and more comprehensive analyses indicate that the current state of privately owned big cats in the United States is likely much improved from what has commonly been messaged even as recently as 2018. Updating our understanding of the distribution of captive big cat populations within the country is crucial to informing accurate and effective conservation programs, legislative actions, and the international credibility of the United States. This document will continue to be updated in the future as more aspects of the historical captive wildlife crisis are examined in light of new information.

Click on a link below to jump to a specific section, or scroll to read them all.

Claim: There are 10,000 - 20,000 big cats owned privately in the United States. This number cannot be verified because most of them are kept hidden from regulatory oversight.

It is highly unlikely that tens of thousands of big cats reside secretly with private owners in the United States. Populations of big cats within the country have never been that large, even before federal, state, and municipal legislation passed that restricted or banned commercial trade in, interstate transport of, or private ownership of big cats. While claims that big cat populations number in the tens of thousands have been common for two decades, supporting data has never existed. The information that can be found (the censuses that do exist, testimony from sanctuaries) documents that the need for rescue is decreasing, and coupled with what can be deduced from indirect evidence, indicates that there are fewer than 5,000 big cats in the United States, with the majority of them residing in zoos or sanctuaries.

For a full explanation, read: “Are There Really Ten Thousand Backyard Big Cats?”

Claim: More tigers live in American backyards than exist in the wild anywhere else in the world.

Claim: There are more tigers in backyards in Texas and Florida than exist in the wild.

Approximately 3,900 tigers live in the wild as of the end of 2018. It is highly unlikely that 3,900 privately owned tigers exist in the United States. While it’s possible that privately owned tiger populations were that high in the late 1980s and 1990s, all available academic data shows that tiger populations across all situations, including zoos and sanctuaries, have only decreased during the last twenty years. Tigers are still the most popular privately owned big cat, but all available data (as well as indirect evidence and testimony from the sanctuary industry) indicates that pet tiger populations within the United States likely number in the hundreds, not thousands.

It is also extremely unlikely that over 3,900 privately owned tigers live in just two states. It is inconceivable that such a high concentration of dangerous exotic animals could be hidden in such specific geographical areas without increased documented sightings, injuries, or escapes. In addition, both states experienced major natural disasters in 2017 that caused a huge amount of property damage over large areas, and no dead or escaped tigers were found, an improbable consequence if such a large number of tigers were living in such a concentrated area.

To Learn More, Read: “Are There More Tigers In Texas And Florida Than In The Wild?

Claim: The number of privately owned big cats in the United States is a major threat to public safety.

Figure 1. Big Cat Safety Incidents by Major Risk Category. From Garner, 2018 (unpublished).

Click Image to View Full Size

Figure 2. Comparison of Big Cat Safety Issues Over Time by Setting. From Garner, 2018 (unpublished).

Click Image to View Full Size

It is not likely that the number of big cats in private hands comprises a safety risk to the general public. Not only has the population of big cats in private hands dropped dramatically in the last decade, but so has the number of incidents in which big cats have escaped, injured, or killed someone. Over the past 18 years, of the approximately 350 total safety incidents involving big cats, more occurred at stationary facilities (48% in zoos, sanctuaries, and attraction involving permanent animal exhibits), than in private non-professional ownership settings (36%)[Figure 1]. The majority of the incidents that occurred in the early 2000s were caused by big cats in private non-professional ownership settings, at a rate of sometimes more than 10 per year, but a marked drop in the frequency of that type of incidents occurred after the Captive Wildlife Safety Act was passed at the end of 2003, and there have been fewer than 3 incidents recorded yearly involving privately owned felids since 2013 [Figure 2].

To See the Incident Data, Read: Big Cat Safety Incidents, 2000 - 2018

Claim: Current regulations designed to control possession of big cat are not successful and have not impacted the number of privately owned animals.

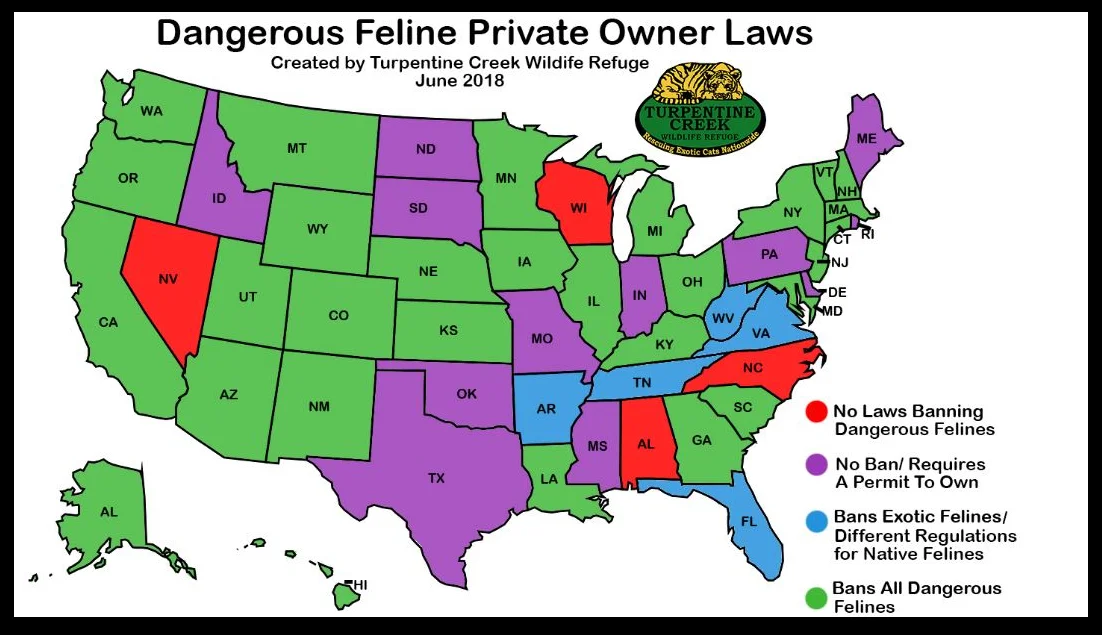

The current set of laws and regulations in the United States have absolutely been successful at decreasing the privately owned big cat population, as well as the frequency with which those big cats hurt or kill people. The Endangered Species Act (1973) banned all importation and interstate commercial trade in big cats. The Captive Wildlife Safety Act (passed in 2003, fully implemented near the end of 2007) banned the transport of big cats across state lines except for specially exempted entities, such as USDA license holders, animal transport companies, and that meet specific criteria. Many states have also passed their own laws [Figure 3] which either restrict big cat ownership (e.g. Texas in 2001) or ban it outright (e.g., Oklahoma in 2003, Ohio in 2012, South Carolina in 2017). Many municipalities and counties in states where it remains legal to own big cats privately also have passed additional laws regarding whether big cats are permitted within their purview.

Figure 4. Big Cat Safety Incidents by Year in Private Non-Professional Settings. From “Big Cat Safety Incident 2000 - 2018”, Garner 2018.

Click Image to View Full Size

The number of safety incidents involving privately owned big cats since the year 2000 has reflected the progression of related laws. Incidents with privately owned big cats were highest in the early 2000s [Figure 4] and occurred all over the country [Figure 5]. After the Captive Wildlife Safety Act was fully implemented in 2007, the majority of the incidents occurring in the United States were related either to single owners with large numbers of resident big cats, or to communities with a large population of privately owned big cats. [Figure 6]. When the map of safety incidents is modified to show only locations where incidents have occurred since 2010 [Figure 7], it is evident that almost all the incidents are clustered in areas with historically large populations of privately owned cats, either before bans were passed (Ohio) or where ownership is either regulated (Texas, Florida) or not controlled by law (Alabama, Michigan).

Figure 5. Big Cat Safety Incidents in Private Non-Professional Ownership Settings, 2000 - 2007 Pre-CWSA

Click Image to View Full Size

Figure 6. Big Cat Safety Incidents in Private Non-Professional Ownership Settings, 2007 Post-CWSA - 2018

Click Image to View Full Size

Figure 7. Big Cat Safety Incidents in Private Non-Professional Ownership Settings, 2010 - 2018

Click Image to View Full Size

For More Information, Read: Big Cat Safety Incidents, 2000 - 2018

Claim: The number of secret and/or unregulated tigers in the United States contributes to the black market trade in tiger parts.

There is currently no evidence that the tiger population in the United States contributes to either the domestic or international black market. During the late 1990s, a small ring based out of the Midwest trafficked in tiger meat and skins; everyone involved was charged with multiple violations of the Endangered Species Act in 2002 at the end of an undercover investigation called Operation Snowplow. Well-known instances of big cat trafficking in the United States, such as the indictments of the owners of B.E.A.R.C.A.T Hollow and Animals of Montana, all appear to have been connected to Operation Snowplow. The large number of dead and preserved tigers and tiger cubs found at Tiger Rescue in California after a raid in 2003 were frequently surmised to be part of a black market operation, but there appears to be no data to support that claim, nor were the couple who ran the facility charged with violating federal wildlife laws.

There has been legitimate concern from the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) that the privately owned tiger population in the United States might be a future risk for contributing to the international black market, but their comprehensive report in 2008 identified no instances in which tiger parts sourced in the United States were used in such a manner. The primary factor contributing to potential future international trafficking identified by the WWF was the exemption of subspecies-hybrid tigers from the Captive Bred Wildlife permitting program, which was eliminated in 2016 specifically due to that concern. When the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) published the final rule regarding the Captive Bred Wildlife program in 2016, they noted that “there is no clear evidence that the U.S. captive tiger population has played a role in illegal international trade,” adding that it was still important to close the loophole due to “the precarious status of tigers in the wild and the potential that U.S. captive tigers could enter trade and undermine conservation efforts.”

A large body of investigative work has been undertaken in recent years regarding the source of tiger parts for international trade; major suppliers in Asia, Eastern Europe, and potentially even South Africa were identified. Investigations by the Wildlife Justice Commission have concluded that there are about 8,000 tigers in farms in China, Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam; a five-year-long investigation by the Czech Environmental Inspectorate uncovered an illegal tiger farm in the Czech Republic with ties to Vietnam. The booming export trade in lion bones from South Africa, along with allegations that some of the Vietnamese tigers were acquired from that country, has led the international community to cast suspicious eyes on the potential contributions of South African’s more than 50 captive tiger facilities. Most claims about the secret privately owned tiger population in the United States alleges that there are more than 5,000 tigers and potentially 10,000 or more - a number equal to or exceeding the total known population among all identified tiger farms worldwide. Parts from American animals entering the international market would not go unidentified due to the close scrutiny black market trade has been receiving in recent years, nor would it make sense for international agencies not to report an influx of tiger parts into the market from a country with such a presumed large and unregulated supply. The fact that the alleged United States tiger population has not even been mentioned in any of the recent reporting about the international black market for tiger parts supports the validity of the statements by WWF and FWS: that there is no sign of the U.S. population contributing to the black market trade.

Read More Articles from Why Animals Do The Thing:

It's fairly common for people looking at elephants to notice that they have liquid seeping from the corners of their eyes. Some advocacy groups say elephants are crying because they're sad, but scientists say that elephants don't have tear ducts. If the latter is true, where is that liquid coming from, and why?