Legislation Breakdown: H.R. 1818 "The Big Cat Public Safety Act"

If passed as written, H.R.1818 would prevent all non-commercial ownership of big cats, and also restrict which USDA-licensed commercial facilities would be allowed to house, transport and breed large felids.

Legislation Breakdown: H.R.1818 “The Big Cat Public Safety Act”

June 15, 2017 - Rachel Garner

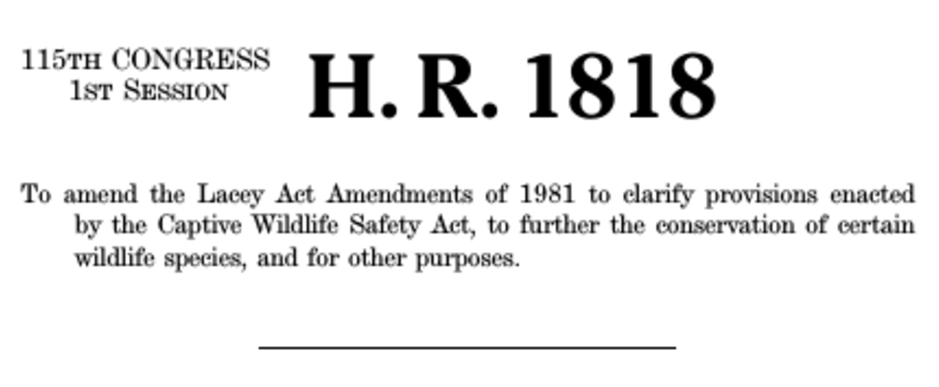

For the purposes of this article, the legislation with the goal of restricting big cat ownership will be referred to as “The Big Cat Public Safety Act.” The proposed bill for the 115th Congress is “H.R.1818” and will be referred to as such when specifics of the current draft are being discussed. Any previous iterations of the text of bills for the proposed Big Cat Public Safety Act from earlier sessions will be referred to by their bill number to reduce confusion.

What Is H.R.1818

H.R.1818 is a proposed bill that would amend the Captive Wildlife Safety Act, which is itself an amendment of the Lacey Act. Passed in 1900, the Lacey Act originally prohibited trade in illegally acquired wildlife that had been illegally taken, possessed, transported or sold, and was the first federal bill to be passed that protected wildlife. The Lacey Act was amended in 2008 by the Captive Wildlife Safety Act, which is what H.R.1818 itself proposes to amend. The Captive Wildlife Safety Act made it illegal to import, export, buy, sell, transport, receive, or acquire big cats (defined as lions, tigers, leopards, snow leopards, clouded leopards, jaguars, cheetahs, and cougars; all subspecies of these species; and any hybrid combination of them) across state or federal borders. Any institution licensed by USDA to own or transport big cats is exempt from those restrictions. If passed as written, H.R.1818 would go much further than the Captive Wildlife Safety Act by preventing all non-commercial ownership of big cats, and would also massively restrict which USDA-licensed commercial facilities would be allowed to house, transport and breed big cats.

What’s in the Current Text of H.R.1818:

“Breed” is added to the definitions section defined as: “‘breed’ means to facilitate propagation or reproduction (whether intentionally or negligently), or fail to prevent propagation or reproduction.”

It is made a criminal wildlife offense for “any person to import, export, sell, receive, acquire, or purchase in interstate or foreign commerce, or in a manner substantially affecting interstate or foreign commerce, or to breed or possess, any prohibited wildlife species.”

Exemptions for the above criminal wildlife offence are given to:

USDA Class C licensed exhibitors in good standing who must also:

Not have had any animal neglect or abuse issues in their history - no fines or convictions - for individual licensed exhibitors, nor any in the history of anyone in the employ of a licensed facility.

Have not had any license or permit applicable to their animals revoked or suspended within the last three years.

Have not gotten any citations under the Animal Welfare Act within the previous year for specifically: inadequate veterinary care, handling that causes stress or trauma or a threat to public safety, insufficient provisions of food or water, or failure to allow facility inspections.

Only allow trained professional employees, trained contractors, accompanying employees in the process of receiving training, licensed veterinarians or accompanying veterinary students to have any type of direct physical contact with big cats.

Ensure that during public exhibition of all big cats (except clouded leopards and cheetahs) or any big cat hybrids that the animal is always fifteen feet away from the public unless there is a permanent barrier that prevents any possibility of contact with the public.

Not breed any big cat species unless the breeding is done in accordance with a “species-specific, publicly available, peer-reviewed population management plan developed according to established conservation science principles.”

Maintain liability insurance in an amount of at least $250,000 for each occurrence of property damage, bodily injury, or death caused by big cats they own.

Have a written emergency plan that facilitates the quick and safe recapture or destruction of big cats in case of an escape that is made available to local law enforcement and state and federal agencies upon request.

State colleges, state universities, state agencies, or state-licensed veterinarians.

Wildlife sanctuaries that care for big cats and must also:

Be a 501(c)(3) corporation

Not commercially trade in big cats or any parts or byproducts of them.

Not breed big cats.

Not allow direct contact between the public and big cats.

Not transport big cats or display big cats off-site.

Entities that have custody of big cats only for transport and are responsible for transporting big cats to another exempted entity.

Anyone who is in possession of a big cat that is born before the date H.R.1818 is enacted and also:

Registers each individual animal with Fish and Wildlife within 180 days of the enactment of H.R.1818

Does not breed, acquire, or sell big cats after the date H.R.1818 is enacted.

Does not allow direct contact between the public and any big cat.

Penalties for any criminal wildlife offense as described in H.R.1818 are a fine of $20,000, up to five years in jail, or both.

Each violation of the rules set forth in H.R.1818 will be considered a separate offense, and will be deemed to be committed not only in the district where it first happened but also anywhere else where the defendant had taken the animal or been in possession of it.

Anyone having been found guilty of an offense under H.R.1818 will be subject to the forfeiture of their big cats.

Any regulations needed to implement and enforce these rules will be created in coordination with the relevant state or federal agencies.

H.R.1818 Content Breakdown:

This section will address the effects of H.R.1818 in the same order as the regulations are listed above.

Defining “Breed”:

The Lacey Act and Captive Wildlife Safety Act do not prohibit the actual act of owning a big cat or breeding it to obtain more. Instead, they only regulate movement or commerce involving big cats across state and federal borders. Currently, it is not illegal under federal law to acquire a big cat from a litter that has been bred within the state in which a person resides or to obtain more big cats by breeding and keeping the cubs of cats they already own. Breeding is not mentioned in either the Lacey Act or the Captive Wildlife Safety Act at all; therefore, the definition must be added through the proposed amendment in order for restrictions on breeding to be part of the scope of the law. The definition of “breed” used in H.R.1818 (“to facilitate propagation or reproduction (whether intentionally or negligently), or to fail to prevent propagation or reproduction”) would hold owners equally accountable for accidental or unintentional litters as for intentionally bred ones. If the owner is not an entity exempted from restrictions set forth in H.R.1818 or belongs to an exempt entity that is not allowed to breed (such as a sanctuary or a Class C exhibitor not participating in a conservation breeding program) they would be guilty of a criminal wildlife offense as detailed above. It remains unclear according to the language in the bill if, in such a situation, the owner would only be charged with one (1) criminal offense - that of breeding - or if they would be charged with another offense per cub born due to birth potentially counting as an “acquisition.”

What H.R.1818 Prohibits:

The next section of the bill sets forth that if passed, it will be illegal for “any person to import, export, sell, receive, acquire, or purchase in interstate or foreign commerce, or in a manner substantially affecting interstate or foreign commerce, or to breed or possess, any prohibited wildlife species.” Whereas the Lacey Act was originally only concerned with banning the ownership of invasive and heavily poached species (none of which are big cat species), and the Captive Wildlife Safety Act simply restricted any sort of commercial acquisition, sale or transport of big cats to within state lines (except for entities who received exemptions), H.R.1818 goes beyond the precedent set by these two laws. H.R.1818 not only completely bans all commercial acquisition, sale or transport of big cats no matter where it occurs, but also makes it illegal for people to acquire big cats by breeding more themselves and actually goes so far as to ban owning them, period. The only exemptions to this complete ban on owning big cats are those entities listed above: USDA Class C facilities (by definition, facilities that conduct exhibition as the majority of their commercial activity), state facilities or veterinarians, wildlife sanctuaries, transport groups, and non-commercial ownership situations that would be grandfathered in when H.R.1818 is implemented. As grandfathered entities are only allowed to keep their extant cats on the conditions that they do not acquire or breed more, H.R.1818 as written will end all hobbyist (pet or “private collection”) big cat ownership in the country and will result in all big cats in the country being part of either a commercial collection, a state-run organization, or a sanctuary.

What Entities Are Exempt:

Most of the text of H.R.1818 is concerned with the qualifications of the entities exempted from the restrictions on ownership of big cats that it creates. However, it’s worth noting that the requirements imposed on different groups in order for them to qualify for exemption are highly inconsistent in regarding ensuring the welfare of the big cats involved. USDA Class C exhibitors have a long list of requirements additional to federal licensure they must adhere to, whereas wildlife sanctuaries have a much shorter and less stringent list, and state entities such as colleges and universities have literally no additional requirements regarding animal use or public contact - they simply need to be state-run.

Class C Exhibitors:

USDA Class C licensed facilities, as mentioned above, must be conducting and receiving a majority of their income from commercial activity: this means they must be open to the public to at least some degree. Both individuals and entire facilities can be licensed as Class C exhibitors after a USDA inspection finds that they are in accordance with the policies set forth by the Animal Welfare Act. At the time of this article’s publication, most of the facilities accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums are Class C exhibitors, but not all of them; the National Zoo in DC and the associated Smithsonian Institution Conservation and Research Center in Front Royale are federally funded and therefore classified as F, and African Safari, which houses the International Animal Exchange, gets a majority of its income from brokering animal sales throughout the animal management industry and is therefore class B. Under the current text of H.R.1818, these AZA-accredited but not Class-C facilities would not be exempt from the moratorium on acquiring or transporting big cats and would not be allowed to participate in AZA’s conservation breeding programs (Species Survival Plans). The same holds true for organizations accredited by the Zoological Association of America (ZAA) that are not Class C exhibitors due to a different source for the majority percentage of their income, both in terms of being unable to acquire or transport big cats and lack of ability to participate in ZAA’s conservation breeding programs (Animal Management Programs). (The most recent previous iteration of H.R.1818 - H.R.3546 from 2015 - included an exemption for AZA facilities and any non-AZA facilities that held an active written contract with AZA as participants in one of their conservation programs. That exemption was removed from the text of H.R.1818 and replaced with the Class C exemption. There has never been any such exemption for ZAA-accredited facilities or conservation programs in any draft of the Big Cat Public Safety Act.) Any unaccredited zoo that is open to the public is also licensed as a Class C exhibitor, as well as any organization that in which warm-blooded animals perform for the public, or are used in educational presentations. This list includes, but is not limited to, circuses, zoos, petting farms/zoos, animal acts, wildlife parks, marine mammal parks, and some sanctuaries. All of these types of Class C facilities must fulfill a list of additional requirements as detailed in H.R.1818 to qualify to receive an exemption from the moratorium on owning, transferring, or breeding big cats.

A Class C exhibitor looking for exemption from H.R.1818 is not allowed to have a history themselves or employ anyone with a history of being convicted or fined for any type of animal abuse or neglect under any level of law. They also may not have or employ anyone who has recently (within three years) had a license or permit related to any sort of animal management suspended or revoked by any level of governmental authority. Both of these regulations appear to exist to make sure that exhibitors are not employing people with a history of abuse, neglect, or unsound practices. Prospective Class C exhibitors also cannot have been cited within the preceding year for any repeat violation under the AWA that deals directly with the most basic elements of captive animal welfare: adequate veterinary care, inappropriate handling that risks harm to the animal or the public, insufficient access to water and adequate nutrition, or failure to allow themselves to be inspected by the USDA. While there are many other things that facilities can be cited for (which comprise a whole range of severity themselves) these are the citations that would most directly reflect the welfare of animals at the facility. A ban on repeat violations means that a facility that was cited once for an issue but found to have corrected it appropriately on repeat inspection would still qualify for exemption, but a facility that had been found to have not corrected an issue after citation and had to be told again would not.

Prospective Class C exhibitors, under H.R.1818, can only allow trained professionals and licensed veterinarians (and the associated trainees and students for both positions) to have any direct contact with their big cats. Direct contact is not defined specifically within the text of H.R.1818 or The Captive Wildlife Safety Act. However, the regulations promulgated in 2007 regarding the enforcement of the Captive Wildlife Safety Act defined direct contact as “any situation in which any individual other than an authorized keeper or caregiver may potentially touch or otherwise come into physical contact with any live specimen of the prohibited wildlife species” - it seem likely this is the definition of direct contact that would be used regarding H.R.1818 even though it is never directly referenced by the text of the bill. This which leaves a large amount of uncertainty about which members of an institution this stipulation applies to: a career big cat keeper who continues to volunteer after retiring would likely still qualify as a trained professional to most people’s thinking, but it is not clear if H.R.1818 would disqualify from potential exemption a facility that allows for that volunteer to continue having contact with cats because while potentially “authorized” as caregivers they’re no longer on the payroll of the institution. H.R.1818’s prohibition against direct contact for anyone but trained professionals means that the number of people at any given facility who are able to assist with training sessions for big cats would likely have to decrease, as volunteers, docents and interns are often highly involved in big cat training but would be unable to participate without disqualifying their facility due to the potential for some form of contact occurring during a training session.

Class C exhibitors looking for exemption from H.R.1818 must also ensure that all big cats (except clouded leopards and cheetahs, for no stated reason - both are listed as a prohibited wildlife species in the Captive Wildlife Safety Act but absent from the list of species this requirement pertains to in H.R.1818) and big cat hybrids must be at least fifteen feet removed from members of the public at all times unless there is a permanent barrier in place that is guaranteed to prevent any and all direct contact. From a perspective related to guest safety, this requirement makes perfect sense - however, a lack of definition of “the public” for this regulation leaves up to interpretation the standing of non-staff with legitimate access to behind-the-scenes areas. Non-public areas of permanent zoological facilities are not constructed with barriers to prevent all physical contact between people and animals, as staff need to be able to have contact with animals as part of regular husbandry routines and as guests are never allowed in those areas without supervision. It’s unclear if this requirement in the text of H.R.1818 would prevent guests from being able to tour back areas that do not have impermeable barriers if the big cats housed there could not be kept fifteen feet away from them at all times.

In order for a Class C exhibitor to be exempted from H.R.1818, it has to be shown that all their breeding is done “pursuant to a species-specific, publicly available, peer-reviewed population management plan developed according to established conservation science principles.” (In previous iterations of the bill (H.R.3546 from 2015 and H.R.1998 from 2013) the only breeding programs exempted were AZA’s Species Survival Plans (SSP) and Taxon Advisory Groups (TAG). In H.R.1818 those provisions were removed.) There are a number of confusing things about this requirement. It is not clear whether a prospective facility had would be required to have already been doing all big cat breeding through such a population management plan previous to the implementation of H.R.1818, or if this requirement simply means that the prospective facility would only have to agree to participate in one of those programs going forward from the implementation date. As many established breeding programs are highly selective about which facilities they allow to participate, an interpretation of this ambiguous text that requires all breeding prior to H.R.1818’s enactment to have been done as part of such a program could severely limit the number of Class C exhibitors that could gain an exemption to H.R.1818. A facility that does not participate in a breeding program appears to still be able to get an exemption from the H.R.1818 regarding the acquisition or transfer of big cats - for instance, in order to house geriatric or surplus cats - but would still be considered to have committed a criminal wildlife crime if an accidental breeding did occur and could lose both their exemption and their big cats to forfeiture.

The proposed text requires Class C exhibitors to be participants in population management programs that are "publicly available" and "peer-reviewed," which poses some interesting questions about what implementation of the bill would require. Currently, none of the main population management plans in the zoo industry (AZA’s SSP and TAG programs, ZAA’s AMP program) are truly publicly available as they’re only accessible through a paid membership to the organization. Since the text of H.R.1818 does not define what constitutes public availability, it is possible that enactment of this bill as written would require all facilitating organizations to remove the program documents from behind the current paywalls so participating facilities would be able to receive their exemption. The peer review requirement is ambiguous, as there is no specific language in the bill regarding what individuals or organizations would be expected to conduct the process of peer review. Peer review generally is generally considered to be a reasonably impartial evaluation of the work done by people of similar competence and expertise to the producers of the work. If H.R.1818 is enacted as written, it seems possible that this requirement could be interpreted in a way that would require peer reviews of populations management plans to be done by people external to the specific breeding program being reviewed, or even external to any organization involved with the breeding of big cats at all. Individuals with appropriate expertise in big cats within the zoo industry would likely be heavily involved in the management plans their facility participates in, so it could be argued that they might not be able to remain impartial enough to provide those programs with appropriate and unbiased critique. There are not many groups that contain professionals with appropriate levels of expertise on big cats to perform peer review of this type that remain external to the zoo industry. As those groups that do fulfill both criteria are often politically at odds with zoos (e.g. wildlife sanctuaries and conservation organizations) this lack of specificity about the intended source of peer review could easily become a very contentious issue if not clarified before the bill is enacted.

Class C facilities looking for an exemption from H.R.1818 would also have to maintain liability insurance for not less than $250,000 for each occurrence of damage caused by any big cat they owned. That sort of liability insurance gets expensive, fast, and might be cost-prohibitive for many smaller or rural Class C exhibitors looking to continue exhibiting big cats. They must also have a written response plan detailing emergency preparedness plans in the case of animal escapes that contain but are not limited to how staff are trained to recapture dangerous animals. This plan must be available to local law enforcement, state agencies, and federal agencies at different points in time. It is not clear entirely clear (from the inconsistent use of the Oxford comma in the text of the bill) if the plan must be made available to local law enforcement at all times and to state and federal agencies upon request, or if all three groups are only able to obtain it upon request.

State Institutions:

The shortest exemption from H.R.1818 in the entire bill states that an entity may be exempted simply if it is “a state college, university, or agency, or state-licensed veterinarian.” There are no other restrictions put on the organizations that would be pursuing this exemption, which seems inconsistent regarding the thorough detail written into the rest of the bill. There are none of the common-sense restrictions on the state exemption that there were on the Class C exhibitors - not even those that prevent people with an animal abuse history from working with the big cats or those that disqualify a facility from exemption for repeated AWA violations. There is also no regulation about if state entities can breed their big cats, unlike that seen in the regulations for both Class C exhibitors and sanctuaries.

It appears this exemption exists (according to written records from a congressional hearing regarding the senate version of the Big Cat Public Safety Act in 2014) because of Louisiana State University’s interest in continuing to be allowed to keep their mascot - a live tiger who lives in a habitat on the school campus. During the congressional session, Louisiana Senator David Vitter’s questions regarding the proposed Big Cat Public Safety Act centered on confirming that a) the bill would allow LSU to keep their tiger, b) LSU would be able to obtain a new tiger to replace their current mascot when he died, and c) ascertain what types of facilities LSU would be able to obtain a new tiger from after the bill went into effect.

Wildlife Sanctuaries:

There are more requirements for a sanctuary to get exemption to house big cats under H.R.1818 than for state institutions, but not nearly as many as those required of prospective Class C exhibitors. This might make sense if the difference was that Class C exhibitors had commercial activity where sanctuaries do not, but that is not accurate to the reality of how modern sanctuaries work or the USDA definition of commercial activity. While H.R.1818 does require sanctuaries seeking exemption to be registered as 501(c)(3) organizations, many of those facilities still conduct commercial activity through advertising and inviting donors to visit and see the animals. Some sanctuaries are also Class C exhibitors (they have robust paying visitorship as well as gift shops and concessions) and it is unclear under the text of H.R.1818 which set of standards for exemption a facility that qualifies as both a wildlife sanctuary and a Class C exhibitor would fall under.

Prospective sanctuaries looking for exemption are required by the text of H.R.1818 to “[care] for prohibited wildlife species” - again, it’s not clear if the facility is required to already have big cats in order to get the exemption or if a sanctuary that wanted to provide a home for big cats could meet all the other requirements in order to get an exemption and then arrange for the transport of the desired animals to their site. They are not allowed to trade commercially in big cats or their byproducts; this calls into question if the common and harmless practice of selling animal pawprints and paintings would be allowed, as those could be considered a byproduct of the animals restricted by H.R.1818. To be exempted under H.R.1818, prospective sanctuaries must not breed big cats. It appears they would be held accountable for any accidental reproduction among their animals in the same manner as Class C exhibitors: at risk of being charged with a criminal wildlife offense, loss of their exemption, and the confiscation of their big cats.

Like Class C exhibitors, sanctuaries are also required to prevent direct contact between the public and big cats. However, the bill does not require sanctuaries to ensure that all staff members having contact with the cats are trained professionals. Sanctuaries are also not subject to the common-sense restrictions that commercial exhibitors must follow, such as those that prevent people with an animal abuse history from working with the big cats or those that prevent employment of anyone who has recently had an animal-related license suspended or rescinded. Why the text of H.R.1818 requires that the staff of Class C exhibitors be so thoroughly vetted but sanctuary staff would not be is unknown.

Last, for a sanctuary to be exempted under H.R.1818, it must not transport or display any animals off-site. The language in this part of the bill is highly unclear - it’s not obvious if the goal is to restrict transport of big cats off-site to specifically exhibition situations or if all travel off-site is to be restricted. The first interpretation would make the most sense - the mission of an animal sanctuary is to give animals a more naturalistic existence that is not subject to human use - but the second interpretation is equally valid under the wording of the bill and would significantly impact how exempted sanctuaries are able to care for their animals. Under the second potential interpretation, all veterinary care for big cats in sanctuaries would have to occur on-site, which could restrict their ability to give animals treatment, as the prohibition against transportation would remove the option of transporting them to specialists. It would also prevent sanctuaries from writing emergency management plans that dealt with transporting their residents off-site in the face on an impending natural disaster or other emergent situations.

Transportation:

Entities that exist solely for the transport of big cats between facilities exempted from H.R.1818 will also be exempt from H.R.1818 in order to be able to do their job. There are no restrictions placed on this type of exemption in regard to employee history - it is not clear why there is no requirement for a history clean of animal abuse charges, although it is reasonable to assume that the authors of the bill assumed that the same level of vetting was not necessary for a temporary transportation situation.

Grandfathered Non-commercial Ownership:

Even though H.R.1818 effectively ends all non-commercial big cat ownership (hobbyist and “private collection” situations) it’s still necessary for any new legislation to grandfather in the ability of current owners to keep their existing cats. Not doing so would cause a massive public outcry, but it would be nearly impossible to enforce the simultaneous and immediate transfer of all big cats from their current non-commercial living situations into the holding of facilities receiving exemption under H.R.1818. As a result, non-commercial owners would be allowed under the text of H.R.1818 to keep any cats born before the date the bill would be enacted. They would also be prohibited from acquiring other cats, breeding their cats, or letting the public have any direct contact with those animals for the rest of the cats’ lives. They would also not be able to sell or give those cats away to any non-commercial entity without being found guilty of a criminal wildlife offense - even if it was because they no longer had the ability to care for them adequately. As the last generation of cats born before the enactment of H.R.1818 die off, the exemptions for private ownership would dwindle as well.

Penalties

As discussed above, every violation of the restrictions set forth by H.R.1818 would be considered a criminal wildlife offense and result in a possible penalty of a $20,000 fine, up to five years in jail, or both. At first, how this would work appears straightforward - selling a big cat as a nonexempt party to another nonexempt party in the same state would result in a single offense for both parties. Since offenses are deemed to have occurred in any district in which the defendant(s) may have been in possession of the animal, it’s possible that each person involved in this hypothetical could be prosecuted for two offenses each: one in the district where the cat originally lived, and one in the district where the buyer resides. If the animal had to travel to get to the buyer, the seller might also be prosecuted for a separate offense in each district they passed through en route. Other methods of counting offenses are less clear. As mentioned above, it’s not clear if someone caught with a breeding violation would be charged for a single offense or with an extra offense for each cub as their birth could technically be counted as an acquisition of an animal. Since the fines and jail time could accumulate so fast in regard to multiple offenses, it seems odd that the wording of H.R.1818 regarding the penalties section has not been fully fleshed out and contains so little elaboration regarding ambiguous situations such as breeding.

In Conclusion

H.R.1818 would implement a number of significant regulatory changes on both commercial and non-commercial big cat ownership in the United States. Of these, probably the most significant are:

Non-commercial big cat ownership (hobbyist or “private collection” situations) would become completely illegal. Current owners of the big cat species prohibited by H.R.1818 would be grandfathered in, but would be prevented from acquiring, selling, or breeding their animals and would lose their exemption with when their animals died.

After the enactment of H.R.1818, aside from grandfathered situations, big cats would only be found in the United States as part of commercial collection, a state-run organization, or a sanctuary.

H.R.1818 would allow for four different types of continuing exemption from the restrictions on commercial trade in or breeding of big cats. The requirements for different entities to gain an exemption are incredibly inconsistent: commercial exhibitors have the most stringent requirements, wildlife sanctuaries have far fewer and less detailed requirements, and transport agencies and state organizations have none at all.

Under H.R.1818, only the staff of commercial exhibitors are required to prove they have a clean record regarding citations or fines for animal abuse or neglect.. Sanctuaries, transport agencies, and state organizations are held to no such requirement.

Unclear language in H.R.1818 could potentially require big cat population management programs to be be peer-reviewed by professionals external to the organization facilitating the program, or even by experts external to the zoo industry.

H.R.1818 includes a provision to exempt state organizations in perpetuity that appears to cater directly to one university’s interest in continuing to have a live tiger live on campus as a mascot. This exemption does not impose any restriction or regulation on how state-based organizations or their licensed veterinarians might use, breed, transport, or acquire their big cats.

H.R.1818 could be interpreted in a way that would severely restrict the ability of wildlife sanctuaries to get their big cats medical treatment, due to unclear wording regarding the restrictions on off-site transportation.

Any entity found in knowing violation of H.R.1818 would be subject to a fine of not more than $20,000, up to five years in jail, or both, for each offense. It is not clear from the text of the bill how the number of offenses committed would be counted in ambiguous situations.

Read More Articles from Why Animals Do The Thing:

For a long time, researchers did agree that Granny (J-2) was probably around 100 years old. They estimated her birth year as being 1911, and that’s still the commonly accepted date that’s listed on most online field ID’s. It’s only the most recent research that points towards J-2 being 80-90 years old.